by Chad Bishop

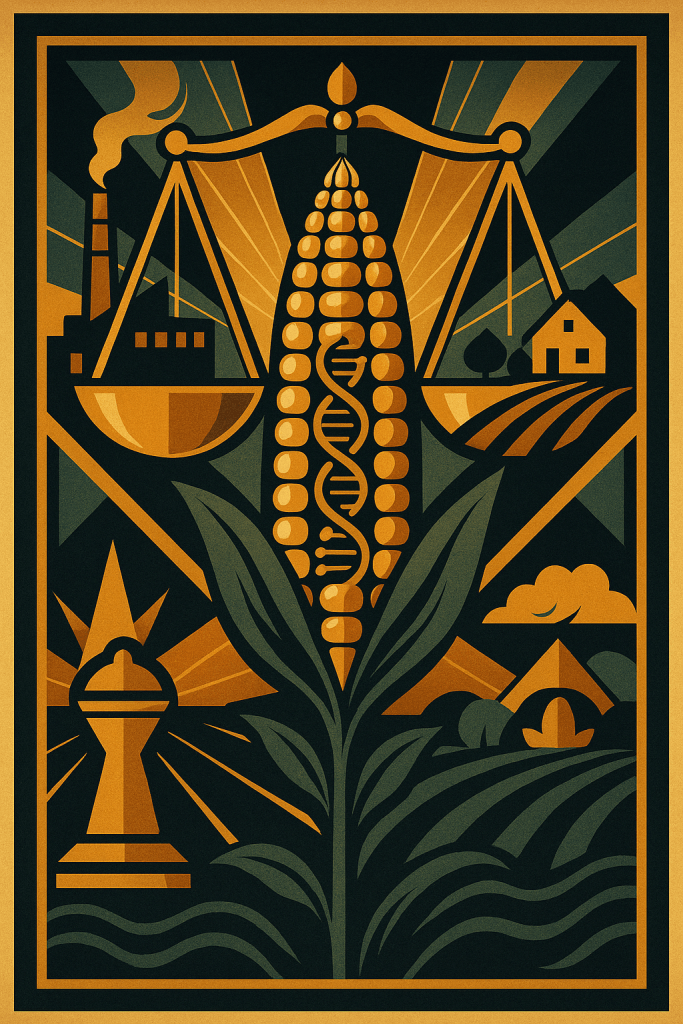

As a high school science teacher I often see students move through their daily routines without thinking much about where their food comes from or how the most basic ingredients in their lunches are shaped by modern biotechnology. To them GMOs may appear as abstract vocabulary words printed in textbooks or talked about in documentaries. Yet these organisms are part of a global conversation linking science ethics culture environment and economics. When we discuss GMOs in the classroom we are not only exploring genetic engineering. We are also examining how societies choose to feed people how they weigh risk and benefit and how they respond to scientific uncertainty.

Why GMOs Seem Promising and What They Offer

The original purpose of genetically modified crops was fairly straightforward. Scientists introduced specific genes into plants to improve traits like pest resistance herbicide tolerance or viral immunity. These modifications help farmers reduce losses increase yields and stabilize production in unpredictable climates.

When GMOs perform as intended the benefits ripple outward. Farmers can reduce pesticide use conserve soil by avoiding repeated tilling and decrease overall fuel and labor costs. This can create a gentler impact on the environment while preserving agricultural output.

From a consumer standpoint GMOs can make food more affordable by limiting crop damage and spoilage. They can also increase resilience in crops grown in difficult conditions which matters tremendously for states like California where drought and heat stress continue to challenge traditional farming practices.

When I teach this in class students often find it compelling that gene editing may help address genuine problems such as food insecurity or disease resistant crops. For many of them it is the first time they see genetic engineering not as science fiction but as a tool for improving everyday life.

The Ethical and Scientific Concerns: What Students Should Understand

Of course the promise of GMOs exists alongside genuine scientific and ethical uncertainty. Teaching this topic means acknowledging complexity rather than simplifying it into an easy good or bad narrative.

Health Nutrition and Long Term Effects

Regulatory agencies state that approved GMO foods do not pose greater health risks than conventional foods while also emphasizing that long term monitoring and ongoing testing remain limited.

Some peer reviewed studies report concerns about increased herbicide use non target species effects and ecological disruptions. These findings remind us that different genetic traits behave differently in real ecosystems and require careful evaluation.

Because genetic engineering covers many techniques traits and organisms safety must be assessed individually rather than assumed across categories.

Environmental Impact and Biodiversity

Environmental consequences often receive less public attention than health concerns yet they are equally important. Crops engineered for pest resistance can affect helpful insects and alter ecological relationships. Herbicide tolerant crops may encourage heavy herbicide use which influences soil health and surrounding plant communities.

There is also the issue of gene flow. GM crops can cross pollinate with non GM crops or wild relatives creating genetic changes in populations that cannot easily be managed or reversed.

For a region like California with rich biodiversity layered ecosystems and environmental pressure from drought these risks carry added significance. Ecological disruptions spread outward affecting farms wildlife and local food systems.

Ethics Equity and Socioeconomic Consequences

Ethical concerns extend beyond biology and ecology. There are also economic and social implications. Many GMO seeds are patented which prevents farmers from saving seeds and increases reliance on large corporations.

Local communities in parts of California have pushed for the right to regulate or restrict GMO cultivation to protect organic farming local biodiversity and agricultural independence.

Students are often surprised to see that GMO debates involve power fairness autonomy and access as much as gene editing. This makes GMO ethics a powerful way to build critical thinking in the classroom.

The Challenge for Educators: Teaching Nuance Not Taking Sides

My responsibility as a science educator is not to decide for students whether GMOs are good or bad. Instead I aim to help them read evidence evaluate claims understand scientific uncertainty and appreciate ethical complexity.

In the classroom this means encouraging students to

Examine GM traits individually rather than generalizing

Think about environmental and ecological effects not just yield or cost

Recognize that scientific conclusions evolve as new data emerges

Respect community perspectives and understand cultural or local concerns

Ask questions about who benefits who bears the cost and who makes decisions

High school students are capable of thoughtful insights when given space to explore. They often ask questions adults overlook and they engage openly with nuanced issues.

GMOs as a Mirror for How We Treat Our Planet and One Another

GMOs sit at the crossroads of science environment economy culture ethics and human values. Teaching this topic in Southern California means acknowledging local agricultural pressures environmental vulnerabilities and the diverse perspectives within our community.

Whether GMOs ultimately serve as tools of climate resilience or become reminders of unintended consequences will depend on how thoughtfully society governs their use. Classroom discussions prepare students for the real scientific and ethical decisions they will face in adulthood.

When we teach students to analyze data respect complexity and consider both risks and benefits we help them become responsible thinkers who can navigate a world where scientific choices carry real weight for communities ecosystems and future generations.