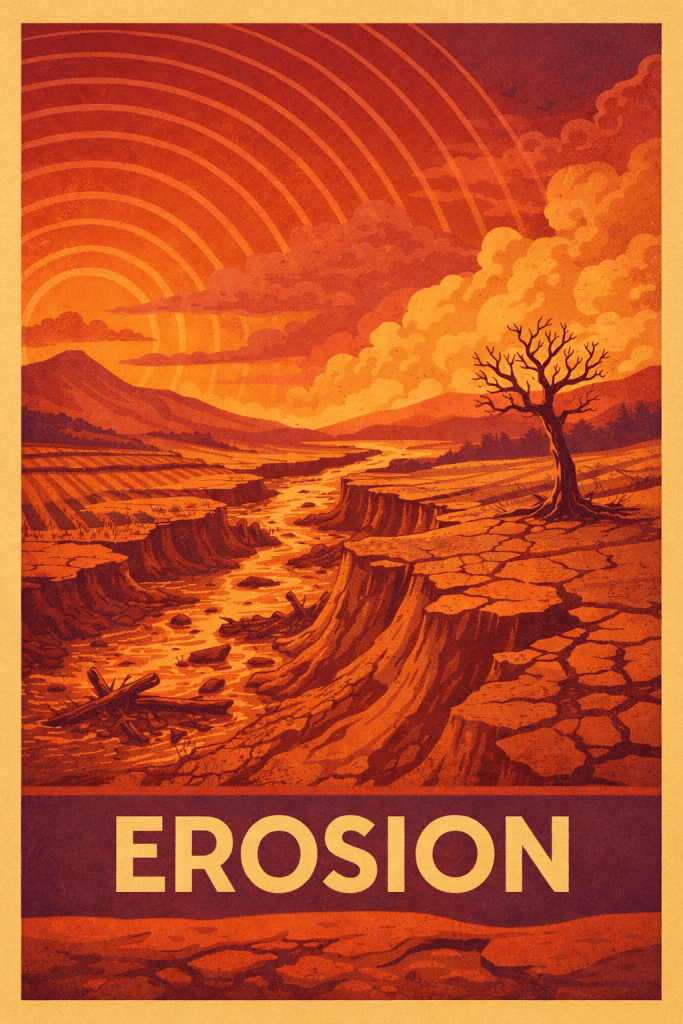

Erosion is one of those topics students think they already understand. Dirt moves. Rocks wear down. Beaches shrink. It sounds simple until you realize erosion is not just a geological process but a long record of human decisions written into the land itself. As a high school science teacher I have come to see erosion as one of the most quietly urgent topics we teach because it happens slowly enough to ignore and quickly enough to matter.

In Southern California erosion is not an abstract diagram in a textbook. It appears in collapsing coastal bluffs disappearing beaches and hillsides that shift after heavy rain. Teaching erosion means teaching patience systems thinking and responsibility all at once.

What Erosion Really is and Why it Matters

The United States Geological Survey defines erosion plainly as “the process by which soil and rock are removed from the Earth’s surface by wind or water flow and then transported and deposited in other locations.” On its own erosion is natural. Rivers carve canyons waves shape coastlines and gravity pulls mountains downhill grain by grain.

The problem is speed. The same US Geological Survey warns that human activities can increase erosion rates “by ten to one hundred times above natural rates.” That statistic alone reframes the conversation. This is no longer just geology. It is acceleration caused by land use choices.

Students are often surprised to learn that erosion does not require centuries. A single construction project that removes vegetation can destabilize soil in one rainy season. Once students see erosion as a process we amplify they begin to understand why it becomes so destructive so quickly.

The Science Students Need to Grapple With

The science behind erosion is well established. Vegetation stabilizes soil through root systems. Natural landscapes slow water allowing sediment to settle. When land is cleared paved or reshaped water moves faster and carries more material with it.

The Environmental Protection Agency states that “sediment is the most common pollutant in rivers streams lakes and reservoirs.” That sediment does not just cloud water. It carries nutrients pesticides and heavy metals with it affecting ecosystems far downstream from where erosion begins.

Coastal erosion offers an especially clear example. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration “coastal erosion is the wearing away of land and the removal of beach or dune sediments by wave action tidal currents or human activity.” When humans build seawalls or harbors NOAA notes that these structures often “interrupt natural sediment movement causing erosion to increase in adjacent areas.”

In the classroom this becomes a powerful systems lesson. Protecting one stretch of coast can worsen erosion somewhere else. Solving a local problem can create a regional one.

Erosion and Equity Who Pays the Price

One of the most uncomfortable lessons erosion teaches is that its impacts are uneven. The California Coastal Commission has warned that erosion and coastal retreat threaten “public access infrastructure affordable housing and environmentally sensitive habitats.” Yet wealthier communities often have the resources to respond while others do not.

The World Bank has noted more broadly that environmental degradation “disproportionately affects the poor who are most dependent on natural resources and least able to adapt.” In erosion this plays out clearly. Lower income communities are more likely to be located near unstable hillsides flood prone areas or aging infrastructure.

Students often grasp this quickly. Erosion becomes a question of fairness. Who gets protected Who gets relocated Who absorbs the loss And who made the decisions in the first place

Why Erosion Is Hard to Teach and Easy to Ignore

Erosion is not dramatic in the way earthquakes or wildfires are. It does not announce itself loudly. The National Research Council once described erosion as a “slow moving hazard” whose impacts are often overlooked until damage is severe.

This creates a teaching challenge. Students live in a world of instant results and erosion demands long term thinking. To make it real we analyze satellite images compare historical photographs model runoff and examine local case studies. We look at how small changes accumulate into large consequences.

What students learn is that erosion is measurable predictable and largely preventable. The tragedy is not that erosion exists. The tragedy is that we often ignore what we know.

Erosion as an Ethical Question

Erosion forces us to confront a core ethical tension in science. Just because we can build does not mean we should build everywhere. Just because damage unfolds slowly does not mean it is acceptable.

The United Nations Environment Programme has stated that “preventing land degradation is far more cost effective than attempting to restore degraded land later.” That statement could double as a moral principle. Prevention requires restraint planning and humility.

As educators we are not simply teaching erosion equations or vocabulary. We are teaching students to think beyond immediate benefit and to consider long term responsibility. Soil that washes away today took centuries to form. A coastline that retreats will not return on a human timeline.

Teaching Students to Notice What Is Disappearing

Erosion in San Diego is not a distant environmental concern. It is visible and measurable along our coastline, particularly in places like La Jolla, where steep sea cliffs composed of relatively soft sedimentary rock are constantly reshaped by wave action, gravity, and winter storms. Coastal scientists and local agencies have documented ongoing bluff retreat in this area, where rainfall infiltrates fractures, weakens cliff structure, and triggers collapses that accelerate shoreline loss. Human interventions such as coastal armoring and development near cliff edges often compound the problem by altering natural sediment movement and drainage patterns. For students, La Jolla becomes a powerful real world case study. The same forces they learn about in diagrams are actively reshaping a familiar landscape, reminding them that erosion is not abstract geology but an active process unfolding in real time just beyond the classroom.

It rarely arrives with drama. It works quietly steadily and persistently. That is exactly why it matters. When students learn about erosion they are learning how human choices interact with natural systems and how small decisions accumulate into lasting change.

Our role as educators is to slow students down enough to notice what is disappearing. When they learn to respect processes that unfold over decades to value prevention over repair and to think beyond their own lifetimes erosion becomes more than an Earth science topic.

It becomes a lesson in stewardship responsibility and the kind of thinking the future demands.